Palace

We find the first written mention of Hohenheim in the gift register of the Hirsau Monastary around 1100. Later, the Bombasts of Hohenheim are mentioned as owners. One descendent of these Bombasts is the famous natural researcher, doctor, and theologian Theophrast von Hohenheim, called Paracelsus.

From the 15th until the mid-16th century, Hohenheim belonged to the Katharina Hospital in Esslingen. Not until 1567 did Hohenheim belong to the Württembergs. After it was almost completely destroyed in the Thirty Years’ War, in 1676 the Augsburg patrician and civil servant of the Empire Emanuel Garb purchased the property. On the irregular foundations of the Middle-Age castle, he built an early baroque moated castle.

1769

In 1769, the Duke Carl Eugen von Württemberg took Hohenheim. Three years later, Franziska von Leutrum, Carl Eugen’s favorite, received the Hohenheim Palace and property from her beloved Duke as a gift.

1776

Starting in 1776, Hohenheim was Carl Eugen’s summer residence. During this time, he changed his style of life and rule. His new life as a withdrawn rural noble in Hohenheim is often traced back to the influence of Franziska von Leutrum. The reason for Carl Eugen’s new style of rule was probably more likely to be found in the changed political situation in Württemberg before the French Revolution. Still, it is remarkable that as of around 1770, he was increasingly interested in the well-being of the countryside, for example the Hohe Carlsschule, the building of roads, the canalization of the Neckar, tree cultivation, and much more. Despite all the despotism that Carl Eugen could never truly get rid of, in Hohenheim he did develop from an autocratic bon vivant to a father of the region.

1774

In 1774, his efforts were successful to have Franziska von Leutrum, “his Franzele,” elevated to a Countess in the Württemberg count in order to make her status befitting to his: Franziska became the Countess of Hohenheim. In Hohenheim, the couple resides in the small Garb residence. Soon they added on living quarters, today the Speisemeisterei, and a building for business matters. In the Hohenheim area, the Karlshof and Klein-Hohenheim, Carl Eugen ran an agricultural estate. It was one of the few ducal operations that turns a profit.

In this time, the so-called English Gardens of Hohenheim were created and were soon respected in all of Europe as a horticultural work of art.

After 15 years of living together, the couple decided to make their relationship legitimate. Carl Eugen intended to protect his partner from numerous enemies at court and in the ducal family. On 11 January 1785, Carl and Franziska were married.

1785

In the same year, the two decided to build a new, large residence palace in Hohenheim. The cornerstone was laid in 1785. Carl Eugen and Franziska oversaw the construction almost daily.

The old Garb residence was turn down, and today’s Hohenheim Palace with the massive corner risalits and large balcony was built over it. On the model of Versailles, a residence palace was to be created whose room axes were turned to the center, the seat of the absolute ruler. At the court of the Sun King Louis XIVth of France, the dominant role of the king was thus embodied, as he shone out into the entire country like the sun. Carl Eugen copied this plan. The architectural model of the Sun King was particularly clear in Carl Eugen’s time with the representative space in front of the Palace. Largely without plants, the space in front of the Palace served to further project the effects of the axes. Only in 1829 was the property on the south side of the Palace turned into a botanical garden. The baroque effects of the Palace and its axes lost even more with the planting of rows of trees. These served to educate the foresters who studied in Hohenheim between 1820 and 1881. Still, even today you can clearly recognize the system of axes in the paths around the Palace.

The new Palace becomes a veritable residence palace with 75 rooms and a massive width of almost 600 meters that correspond roughly to the distance between the Stuttgart Main Train Station and the Palace Square (Schlossplatz) today. It took many years to be built. After eight years, the shell construction and interior construction of the East Wing were finished. However, in the West Wing, the wall decorations, floors, ovens, and windows were still missing in many rooms.

1793

With the construction at this stage, Duke Carl Eugen died in October 1793 in the couple’s temporary residences, in the Mansarden level of today’s Speisemeisterei Wing. Although Carl Eugen ensured that his “Franzele” was well-provided for in his will, the ducal family drove her out of Stuttgart, viewing her as an illegitimate upstart. Even though she had been the legal Duchess of Württemberg since 1791, Franziska was forced to live withdrawn from court on her personal property in Sindlingen and her widow’s seat in Kirchheim Teck. In 1811, Franziska died in Kirchheim Teck, 18 years after her beloved “Carl Herzig.”

After Carl Eugen’s death, construction on the Hohenheim Palace is essentially stopped, and later the Hohenheim Palace is even plundered for material for the New Palace in Stuttgart. For 25 years, it stood empty as an imcomplete construction site, and its destruction was even considered.

1816

Between 1816 and 1817, after two almost complete failed harvests, there was famine, poverty, and embitterment in Württemberg. This situation was politically dangerous for the young royal couple Wilhelm the First and Katharina Pavlovna, who had just acquired the Württemberg throne. Quick countermeasures were called for. Queen Katharina took care of immediate concerns with welfare work. In order to ensure continual and sufficient provision of food to the population, however, farther-reaching economic reforms were necessary. King Wilhelm was busy with these. First he founded an agricultural society with a central office in Stuttgart, and on 20 November 1818 an Agricultural Institute in the abandoned Hohenheim Palace. With this, he laid the cornerstone for the current University of Hohenheim.

In the central section of the Palace and around the central and Western courtyard were lecture halls, labs, libraries, and apartments for professors and students. The Eastern courtyard was used by the institutions of the estate business and agricultural school belonging to the institute. In the Southern wing of the Eastern courtyard, you could find the Chemistry section and agricultural technology with larger workshops and labs. For over one hundred years, this use of the Palace remained largely unchanged.

1957

Toward the end of the 1950s, the Palace area underwent reconstruction. Between 1957 and 1967, the buildings around the Western courtyard were torn down and rebuilt in their old forms but with modern construction materials. The same was done bewteen 1969 and 1970 with the wings in the Eastern courtyard and a wing in the central area.

1967

Finally, in 1967 renovations on the central building of the Palace were started. They continued until 1986. The historical Speisemeisterei wasn’t even finished until 1993. With these renovations, the historical elements of the Hohenheim Palace, which is unique in many regards, were retained and yet could fulfill the requirements of a modern university.

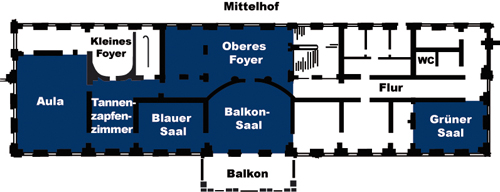

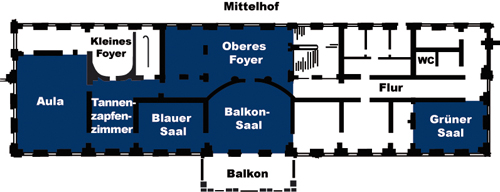

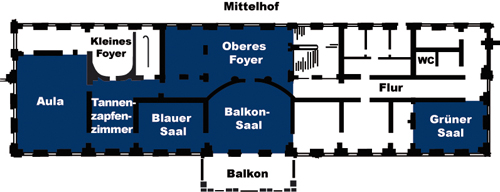

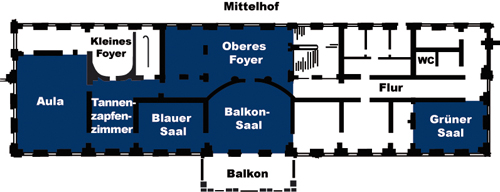

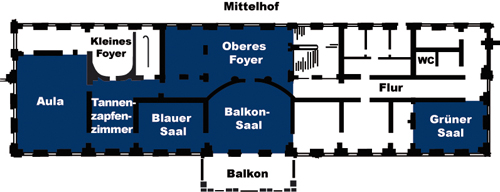

Floorplan

Ground floor

Upper floor

The new Hohenheim Palace was originally intended to be the summer residence of Duke Carl Eugen. With a length equivalent to today’s distance from the Stuttgart train station to Palace Square, and with three courtyards, it was then one of the largest palace buildings east of the Rhine. It was not a completely functional residence because it was still missing several state apartments.

Carriages arriving from the South drove directly under the balcony into the lower foyer. Thus, the royal party could enter the palace with dry feet and climb the stairs to the Bel-Étage.

The ground floor accommodated the ducal art gallery with its approximately 470 paintings. After Carl Eugen’s death, the paintings were transferred to other palaces. br />

During the 1960s and 1970s, the rooms on the ground floor were renovated so drastically that nothing is left of their original grandeur.

Noteworthy is the cornerstone of the palace bearing the date 1785; it can be found on the left beside the stairs up to the first floor.

Ground floor

Actually, this palace cellar was not a cellar in the usual sense but a substructure, or in other words, a foundation for the palace itself. This substructure served to protect the walls of the palace from the very moist soil. In order to increase the stability of the construction, the load-bearing arches were filled with construction debris. That explains why the cellar could not be used at all until the second half of the 20th century.

Ground floor

The upstairs foyer reflects the second half of Duke Carl Eugen’s outlook on life: his withdrawal into the life of a country gentleman is symbolically represented here. Note how the decorative mouldings have primarily country themes such as fruits, baskets and garden implements. The statues of the four seasons have a similarly bucolic character.

But the asymmetry of the upstairs foyer is not typically Baroque. The foyer can only be reached from a stairway on the east side. The west stairway had indeed been planned and the necessary space is there even today but because of the duke’s death and the resulting halt in construction, the second staircase was never put in place.

From the upper foyer, one has a very good view of the large centre courtyard of the palace, which had been conceived as a forecourt.

Upper floor

As originally conceived, the center hall of the palace was intended to be the focal point of the residence. This is where the duke was to hold court. But since this hall was not finished until after Carl Eugen’s death, it never served for any of the duke’s celebrations or receptions.

Later in the 19th century, this room served as a place for meetings and assemblies of the Agricultural Institute. The wall decorations and the ovens were removed and the entire room was painted an “academically sober” white.

From the sketches that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe made in his diary when he visited Hohenheim in 1797, we can see that at that time, the room enjoyed magnificent wall decorations. It was only after restoration began in the palace that remnants of the original alabaster were found under the plaster--colorfully patterned wall tiles, marble moldings, and brightly finished wall decorations.

Using alabaster from the Rems valley and the Löwenstein mountains, the original character of the room was restored. As a result, the university now has a magnificent room for ceremonial events and an object of much envy.

Upper Floor

When Johann Wolfgang von Goethe visited Hohenheim in 1797, he noted in his diary that construction was taking place in several rooms in the west wing.

While he was disappointed and even scandalised by the rococo-style decorations on the east side of the palace, he was impressed by the work of the Schwabian classicists, Isopi and Thouret: “Since part of the palace is not yet completed, it gives hope that (Isopi and Thouret) will succeed with their decorations”.

In fact, the few rooms that had been completed by 1797 are characterised by a completely different, classic style.

The ceiling frieze that gives the room its name is not decorated with pine cones but with what are probably either hops umbels or artichoke blossoms.

Upper Floor

The auditorium is also one of the rooms which was expanded in the new classical style in 1797.

Particularly striking in this style are sober, clean lines and the dominance of the space - in marked contrast to the majority of the playfully embellished rococo-style rooms in the east wing.

Today this room is used for meetings and events at the University. The preservation of the historic spatial effect is combined perfectly with the technical requirements of a modern conference room.

Upper floor

This space had been changed so much over time that nothing more of its original form was known until the renovations around 1970.

During the restoration, however, remains of the original decoration were discovered under the layer of plaster: painted valances and simulated architecture adorned the walls. An example of this can be seen in the small piece of the original exposed on the west side of the room, right above the entrance door. The room was then reconstructed according to these patterns. Thus, the Blue Room is now very similar to its original 18th century state.

The dominant color in the wall paintings give the room its name today. Today the Blue Room is a popular venue for university events.

Upper Floor

Originally, the Green Room had been designed as a bedroom for the Duke. But Duke Carl Eugen never slept here - when he died, although the decoration was already completed, the splendorous bed had not yet been delivered.

It is sometimes saud that Hohenheim Palace is one of the most cost-effective palaces Carl Eugen built - his bedroom has a floor area of nearly 120 square meters - nowadays the area of a four-room apartment. The Palace was not designed to be compact.

The room, formerly used by the Agricultural Institute and as official residences, now houses the Departmental Library for Economic and Social Studies. The rooms were then divided by partition walls and the ceiling was set lower by about 1.5 meters with a false ceiling. The 'old' wall decorations were removed below this ceiling and the rooms were furnished according to the taste of the times. Thus, all of the original wall decorations were lost. However, the original ceiling, which was located above the suspended ceiling, remained preserved and was able to be largely restored.

Today, this room serves as a conference room where the important committees of the University also convene. The fact that this room was originally designed as a place to sleep is pure coincidence and has of course nothing to do with the current use.

Upper floor